If I actually wrote about XOXO 2018 last weekend like I had intended to do, I would have tried to write an article titled "XOXO strives to be what the internet should strive to be," and I probably would have never finished it. It's not that I don't still think XOXO tries to be what the internet ought to try to be; rather, it's that I have a misguided desire to separate what I feel from who I am, especially when I am creating, so that my words could find some unattainable universality and divorce themselves from my not particularly important existence compared with people substantially more eloquent and interesting.

This is particularly ironic for me in the context of XOXO. I've been lucky enough to get to go to every XOXO since 2014, and people I've met in XOXO's community have consistently valued my personal experiences and reminded me that I am happier and create better when I bring my whole self to creating.

It's even more ironic when I think back on the talks at this past XOXO, especially the one that resonated with me the most: Open Mike Eagle's discussion of his creative process and how difficult creating can be. Much of his talk was devoted to how he struggles to explain his creations to others when he himself is still not entirely sure how to succinctly describe the work he's created. He also touched on how creating with an eye on how an audience will receive what you're creating can hinder creating itself - the precise problem I narrowly dodged by procrastinating writing this essay!

***

XOXO Festival describes itself as "an experimental festival for independent artists and creators who work on the internet." This year's festival was my fourth XOXO, and the first one where I felt I could claim the words "independent creator" as words that described me. I finally had not just one non-trivial independent project, but two! I make two podcasts! Podcasts are on the internet! I could put things I was proud of on my badge! I finally felt like I created real things that meant I really deserved to be there, instead of being that person who was still working on creating the metaphorical space in their life for creating, someone who snuck in and was twiddling their thumbs until someone noticed.

This year's festival was attended by nearly twice as many people as the other three I've had the fortune of attending, and it was the first festival since I started to help moderate XOXO's lively Slack community. I don't know if it was because of either of those things or because of something else, but this festival was somehow the first one where I didn't feel like my creating brought much to the festival. I had substantially fewer conversations about what other attendees were working on, what I was working on, and creating in general than at past festivals.

XOXO was also at a new venue located in a different area of Portland, one much less surrounded by a bunch of restaurants within walking distance, and despite the increased in attendees, there didn't seem to be an increase in food carts on site. The Andys (Andy Baio and Andy McMillan, the festival's creators) put in extra work to prioritize businesses owned by chefs of color, which is fantastic, and I'm sure worrying about the budget deficit didn't make it any easier to coordinate with the vendors they did secure. Unfortunately, the vegetarian and vegan options ended up being very limited, and there wasn't breakfast other than Pip's (delicious) donuts on site like there was in previous years. Between eating most meals offsite because many of my friends at XOXO are vegetarian or vegan, not having the excuse to meet up on site for breakfast before the talks, and getting to the main stage early because many of the seats weren't comfortable for myself and my friends, I found myself finding very little of a specific, rare type of serendipity in meeting awesome new people I had come to associate with XOXO.

***

XOXO Festival may describe itself as "an experimental festival for independent artists and creators who work on the internet," but for many people, especially marginalized people, XOXO is a lot more than interesting talks and performances by highly talented artists and creators: it tries - and often succeeds - to create a safe space for those traditionally left behind. XOXO has had a strong community code of conduct since at least as long as I've participated, and the Andys have discussed its enforcement openly at the festival and within the Slack community. But it takes a lot more than a solid, enforced code of conduct to create that sort of space. It requires recognizing your biases and actively thinking about inclusion - prioritizing diversity when creating the lineup; a fairer registration policy than first-come, first-served through surveys collected over more than a week; caring about physical, emotional, and financial accessibility; normalizing socialization without alcohol through the extensive, free non-alcoholic drinks menu while charging for alcohol; denormalizing assumptions like gender and pronouns through pronoun pins; and confronting the history of the lands you're standing on and the people you've displaced.

I used to joke that my gender was "a woman in tech" because I've never truly felt like a woman outside of society gendering me as one. During the past few months, I've come to realize I'd been hiding my feelings about gender behind humor. Demi Adejuyigbe brought an excellent talk on hiding behind humor to XOXO 2018, and one line really stuck out to me:

If I make fun of me, then it won't matter when other people do.

Demi wasn't speaking about gender, but when he spoke that line, feelings about how I've previously interacted with my gender flooded my existence. If I said that I was a woman, then it wouldn't hurt me when other people did.

I started to understand that I am non-binary, probably primarily agender, in no small part because of the space the XOXO community provides me to safely be who I am. For a time, XOXO was the only space I was actively out in. While I continue to deeply feel that acceptance and safety within the XOXO community Slack, I didn't truly feel that safety deep in my gut at the festival. If I sat and thought about it, I felt safe because I had my partner Matt and other friends who would help me navigate potential issues and because I felt the Andys would take those issues seriously, should something happen.

But it was a very intellectual form of safety, not the instinctual one I'd known in the past. Maybe it was the lack of gender neutral bathrooms that was corrected slowly as the conference went on, and being involved in figuring out how to fix that oversight took no small amount of emotional labor and energy from me, someone who was directly hurt by it. Maybe it was what seemed to be an increase in white tech dudes, many of whom complained about XOXO's inclusion of content warnings because they thought it was "simply 'for independent artists and creators who work on the internet'" - as though that isn't descriptive enough because XOXO tries to value and prioritize marginalized people.

***

During past XOXOs, I have always cried - sometimes during talks, others back in my hotel room after experiencing days where I've felt radically seen as a person in ways I am not used to. But I'm the sort of person who cries a lot, and I've come to accept and expect that.

I didn't cry during XOXO 2018. I did cry a little after I flew home.

It's not that I didn't enjoy my time at XOXO - I did. I got to see a bunch of close, old friends, and I got to spend time in person with some newer ones. I listened to a bunch of fantastic talks, saw truly excellent performances, and played a variety of engaging arcade games. I just wasn't expecting the expectation mismatch after experiencing three other XOXO festivals.

***

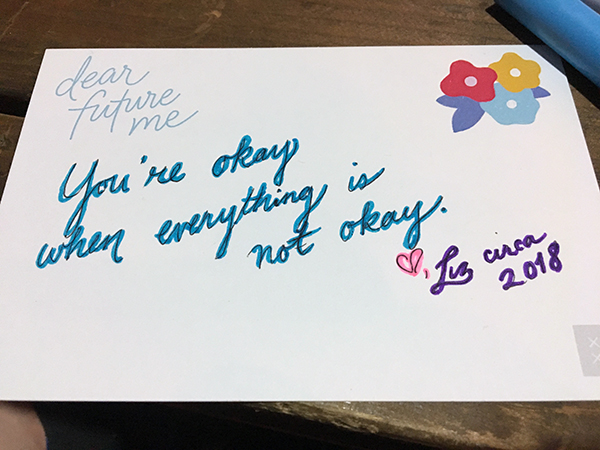

A week before this year's XOXO, another attendee started a lovely discussion about being a survivor by asking:

What's a motto that holds meaning for you? A line from a book or song or movie that expresses the difficulty of learning to thrive after years of surviving?

I immediately thought of a line I love from a Tori Amos song I don't really love anymore:

I'm okay when everything is not okay.

***

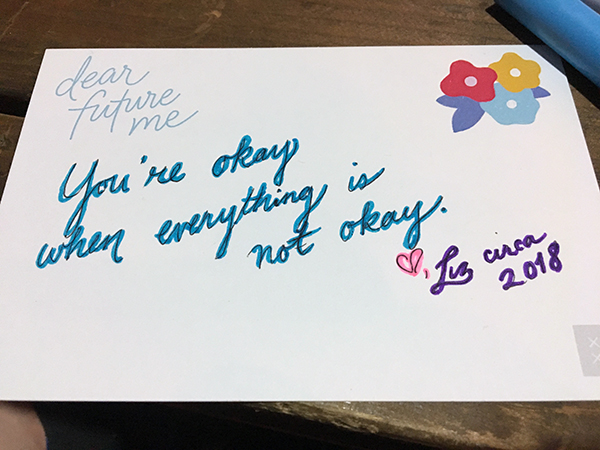

After the closing concert (Lizzo was incredible, by the way), I finally made my way to Dear Future Me, Alice Lee's interactive mural installation. Participants wrote postcards to their future selves that will be mailed a year later.

I knew I wanted to participate, but I kept putting it off because I didn't know what I wanted to write. I kept worrying about who future me would be, and how they would receive my letter. Plus, many of the participants wrote more eloquent and interesting letters than I could ever write.

So when I finally sat down in the calm environment Alice created to write my postcard as the festival was drawing to a close, my brain jumped around all the things that felt off that weekend. How I felt so different from how I had imagined I would have felt. How I didn't quite feel okay.

Then, it hit me, and I smiled.

Dear Future Me,

You're okay when everything is not okay.

♡,

Liz circa 2018