Recruitment is one of those things that everyone does, but everyone seems to want to do better. It's also the kind of thing that is challenging: it's complicated, it's tiring, and it's personal.

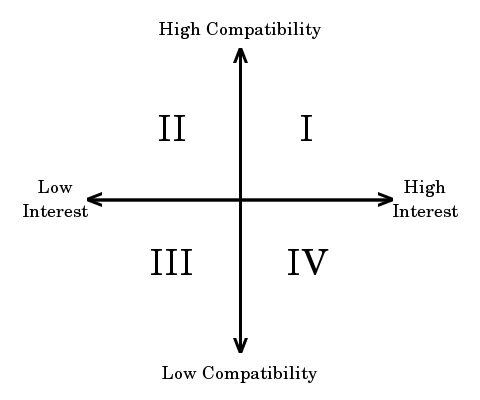

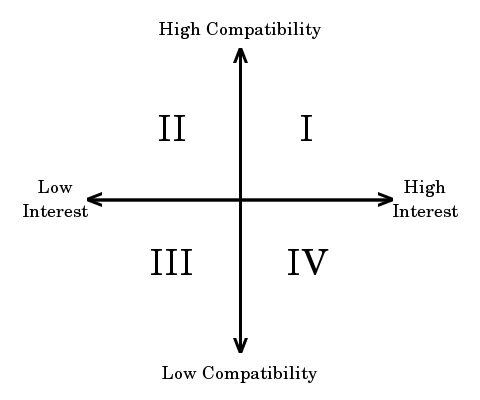

Even if the {company, organization, student group} you're recruiting for has {well-defined, narrow} common goals or interests, the people you will want to recruit aren't likely to fit into any one "type." Primitive "typing" (computer pun not intended) can be based upon a two-axis plot of their interest and their compatibility.

To clarify, compatibility refers to their interest in what your organization does, while interest refers to how interested a person is in joining an organization surrounding those interests.

Last Thursday, I ran a discussion-based workshop on recruitment for SIPB, MIT's computing club. In the context of SIPB, "compatible'' refers to how interested in or knowledgeable about computing a given person is, and "interested'' refers to how interested they are in being a part of a computing organization. I introduced the types mentioned above as a foundation for what I hoped to be a very organic and free-flowing conversation about improving recruitment. Turned out my plot worked.

To start, we discussed some of the reasons that people walked into the SIPB office. They included:

- wanting to learn about SIPB,

- desiring use of a stapler, hole punch, or scanner,

- attending a hackathon,

- needing help to fix a computer problem,

- hanging out with friends who spend time in the SIPB office,

- tooling on a pset with SIPB members, and

- proving to a reasonable portion of zephyr that you exist outside of the terminal.

We then talked briefly about how likely some of these people were to fall into the various types and emphasized how SIPB's recruitment efforts needed to be tailored not only to the different types of people but the different reasons they came into the office. It's a bit strange to spontaneously sell someone on the organization who's just using the stapler, but it's almost logical to inform them of some of the organization's other services.

We found that there was a central theme to what we wanted to accomplish with any interested or compatible person: we primarily wanted to get them to come back to the office. Ultimately, this accomplished more than just keeping someone informed through a set of mailing lists (which they could then filter to an ignorable mail folder): the returning prospective member gets more personalized attention and another opportunity to see the awesome things the office is up to.

We let the conversation flow pretty organically, and some of the other suggestions to reach out to prospective members and to get them involved in the organization included:

- maintaining a running list of "smaller" tickets which don't require a lot of background knowledge but relate to SIPB projects,

- emailing prospective members about parts of projects or new project development that have low barriers to entry,

- updating the website to contain information relevant to prospective members in a clearer, more direct manner,

- making a point to introduce yourself to an unfamiliar face that sits down next to you,

- pointing people towards other members whose interests are better aligned to theirs, and

- following up with someone you talked to for a bit but haven't seen in the office for a week or so.

My observations of the SIPB office over the course of the weekend indicated that some of these are already well on their way to implementation.

The final topic of conversation revolved around how to get people who might be interested in an organization like SIPB but have never set foot in the office to learn more about SIPB. Of course, we mentioned inviting computing types to hackathons and other events. I suggested that subtler methods could be even more effective; I know that I've gone to the SIPB office many times simply because someone asked me where I was headed after class and mentioned they were headed that way.

We certainly didn't touch on everything which could be done to improve recruitment for SIPB; after all, recruitment is not just a hard problem, but one that changes over time as an organization, its members, and its prospective members change. But I also never expected to hold this workshop just this once.

***

I didn't write up too many of the notes about the various types here because they were fairly specific, but I did address it briefly in the comments section of my old blog:

Paul: I liked the two-axis model a lot, and I was hoping you would have talked about it a bit more. To ask a very open-ended question: What should a group do about/with type III people (low interest, low compatibility)?

Me: I intentionally didn't speak too much about it directly because how you handle people in types II and IV - the two groups one usually needs to spend the most time thinking about with respect to recruitment efforts - varies significantly from organization to organization. In terms of type III, the main goal is to be informative. People in this group can move to type II or IV fairly easily. In terms of SIPB, this is about informing people about services like scripts, linerva, and XVM, or if it comes up, mentioning that Debathena is a joint effort between SIPB and IS&T. Hearing about how SIPB's services makes their lives easier might make them think of SIPB in a more positive light. They also might tell all their friends about the awesome services we provide - maybe some of their friends will want to get involved!