Popular Twitter parody account @BabyYodaBaby is currently suspended for "platform manipulation and spam" according to their Instagram. Twitter's policy on platform manipulation and spam allows for "using Twitter pseudonymously or as a parody, commentary, or fan account," as @BabyYodaBaby is doing. This is the second time @BabyYodaBaby has been suspended, and they've mentioned they've appealed the decision. However, despite being an extremely popular account with over 200,000 followers, they've stayed suspended for a week.

First, a brief (unrelated) tale of a Twitter suspension

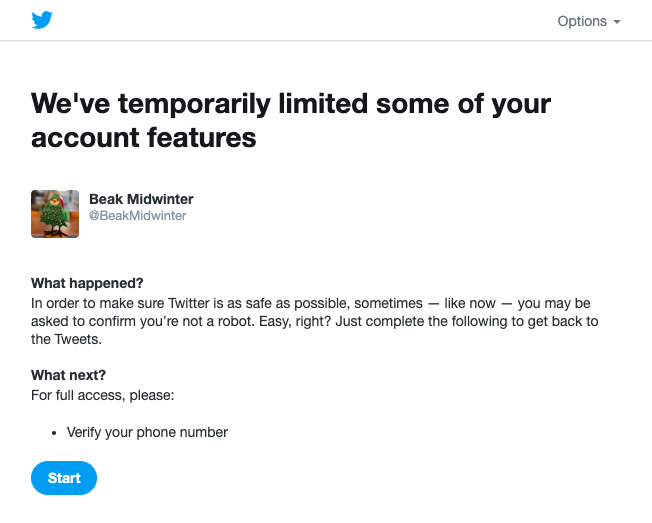

Last December, I created a new Twitter account for a festive holiday birb, @BeakMidwinter, to test whether or not you could create a Twitter account without giving Twitter a phone number. Beak Midwinter is a fictional persona I created for a delightful holiday bird decoration to spread general winter joy and also likely falls into the broad "parody account" category. When you create an account, you can either use an email address or a phone number, and I opted to use an email address. After creating the account, I immediately added basic profile information, a first tweet which I then pinned, and set up two-factor authentication via both an authenticator app and a security key. Beak followed a few accounts, and some of those accounts, not just me, followed them back. Their first tweet was liked. All in all, @BeakMidwinter started off like many other accounts - parody or real person - would.

Within an hour of creating the account, @BeakMidwinter was "temporarily restricted," and Twitter gave no reason behind this action. When I logged in, I was greeted by text telling me "what happened":

In order to make sure Twitter is as safe as possible, sometimes - like now - you may be asked to confirm you're not a robot. Easy, right? Just complete the following to get back to the Tweets … Verify your phone number.

I couldn't find anything @BeakMidwinter did in violation of the associated Twitter Rules or Twitter Terms of Service. When I tried to log into @BeakMidwinter's account, I was told I could remove the restrictions by adding a phone number, just as the help pages implied. I wasn't going to do this because I didn't want Twitter to be able to trivially link this account to my phone number's advertising profile. Plus, Twitter has a bad track record of using phone numbers that we're given for security purposes, which makes me even more suspicious of giving the company my phone number.

A few weeks later, @BeakMidwinter's temporary restriction changed to a suspension: they didn't give a reason, but I suspect it happened automatically because I didn't add a phone number to the account. I appealed the decision, stating the following as the description of the problem:

My account was banned simply because I did not want to add a phone number, which can be used for marketing purposes. This account is an account made by a real person in order to spread holiday joy through the fictional persona of a delightful felt bird who sports a decorated tree costume. I have searched the Twitter support pages extensively, especially https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/twitter-rules, and found nothing that would ban this account. This bird persona is not impersonating anyone or manipulating the platform, just attempting to spread holiday cheer.

I revealed myself, "Liz Denys, the human behind @BeakMidwinter," in the full name field and did not fill in the part of the form that (optionally) asks for a phone number. Twitter sent an email to the email on @BeakMidwinter's account requesting I "reply to this message and confirm that you have access to this email address," and I did. Twelve hours later, Twitter removed @BeakMidwinter's suspension, and the festive birb has been tweeting good winter vibes ever since.

So, you might wonder, what does a little account like @BeakMidwinter have to do with @BabyYodaBaby?

It's not clear that @BeakMidwinter was suspended for any reason other than Twitter testing how far the account would be willing to go to avoid giving the company a phone number, but if there was any section of the rules that Twitter could argue my little festive birb parody account was violating, it is the "platform manipulation and spam" section.

I'm not an expert on account policies, but some very normal Twitter behaviors are only protected through exceptions. Anyone who has a separate account for their business, organization, or project runs the risk that they "artificially amplify or disrupt conversations through the use of multiple accounts" through "coordination," save the exception for "operating multiple accounts with distinct identities, purposes, or use cases," which explicitly calls out organizations, hobbies, initiatives, and pseudonymous alt accounts. Even "engaging (Retweets, Likes, mentions, Twitter Poll votes) repeatedly with the same Tweets or accounts from multiple accounts that you operate" counts as "coordination," even though it's natural to like your project's tweets. (I already don't "like" tweets on my main Twitter account for other reasons, mainly because Twitter doesn't store like data in a way that I control, but it turns out this choice helps protect my accounts from being penalized for "coordination," too.)

This all assumes @TwitterSupport applies their rules carefully and fairly. Based on my experiences and reading those of others, suspensions happen without warning, and you are then at the mercy of Twitter Support understanding and agreeing with your appeal. Even putting Twitter's mishandling of suspensions of marginalized people aside for a moment - something very important and worth discussing - it's baffling to me that my barely active, tiny festive birb can overturn their suspension while @BabyYodaBaby, a wildly popular account that actually drives some traffic to Twitter, has been suspended without anything besides being told their account is used for "platform manipulation and spam."

One possible Twitter future

Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey has recently stated a desire to decentralize the platform, which sounds a lot like Mastodon's Fediverse to me:

I have a sinking suspicion that a decentralized future for Twitter might start by removing the exceptions in their platform manipulation and spam policy. Maybe first, we'll lose harmless bots, such as those broadcasting information about the weather or code commits, because they will be relegated to their own separate site with its own set of rules. I won't be surprised if "parody accounts" follow. Then, separate instances for projects and organizations. (Maybe also, businesses, though ads from whatever Twitter instance is created for brands will be shown across instances.) Next, pseudonymous accounts, including accounts incorrectly marked as such.

I'm not going to say every account on Twitter is intrinsically valuable, but I've found value across all these very different types of accounts. Verified accounts already, fairly arbitrarily, make some of us second class citizens. I'm not intrinsically opposed to decentralization - people should have options, and I'd certainly rather be on a platform that penalizes accounts that engage in hate speech instead of accounts calling those people out - but decentralizing an established platform will require a level of care that Twitter hasn't shown on its existing, singular platform.